Hilarious random plot generator. Answer a few quick questions and this website will automatically write a story or blurb for you using your keywords. Select from a variety of genres including romance, mystery or teen vampire. Plots suitable form books or films. The Stage Plot The stage is the white area on your browser that initially writes 'drag and drop your objects to the stage'. This symbolizes the true stage for your live concert and/or show from the audience perspective. Therefore, you can place objects on the stage and create your Technical Rider within just a few minutes. Add objects to the.

Judy has written this guide to drafting your light plot:You may be drawing your lighting plan by hand, or using a CAD (Computer Aided Drafting) program. The basic principles are the same, though the CAD programs may have shortcuts which will help with some of these stages. In any case you should understand the basic method.

Stage plot software: Band Helper (Android app) Stage Plot Designer (free) Stage Plot Maker (for iPhone and iPad) StagePlot Pro (best software but costs $5) Tecrider (free) Input List Creating an input list (article + free template). Developing perfect stage plan (aka stage plot) for the show Many clubs in our area are requesting band rider and band stage plan. I recently had to provide a detailed plan for a show, and it was a pain to come up with the good stage plan. Stage Plot Designer. Print To save PDF, choose 'Save as PDF' from list of printers, devices, or destinations. SHOW DATE / TIME.

- Preparation

You will need:

- A scale plan of the set. This almost always includes architectural features of the stage as well: rear and side walls if they are close enough to be relevant, and the sides of the proscenium arch. However if you are given a plan of the set which does not include these, you will have to add them, to the same scale. The idea is to have a scale plan which includes all important physical features of the area you need to light.

- A ceiling plan of the theater. If the theater has a fixed grid this should be a plan of the grid. If it has electric pipes which are raised and lowered you will need to know where all the pipes are. The ceiling plan must be to scale; if it isn't, you will need to find out the exact locations of the lighting positions so that you will be able to add them to scale in your lighting plan. You will also need to know the exact height of all lighting positions.

If the theater has a fixed front of house bridge this information might be difficult to obtain, but you should try. In a properly designed theater the angle for front of house lighting is about 45 degrees but there are theaters which are not well designed and the angle might be steeper or shallower. If you can't get exact information, you might be able to turn on a fixture from the front of house bridge, and then you will be able to measure the size of area it covers. You can also measure the angle by drawing a section: Put a friend in the center of the light, and draw a stick figure to scale of the friend, and draw the beam of light on the floor: you will see the angle from the person's head to the shadow of their head.

- A list of lighting elements. You will have prepared this during rehearsal (see 'Two Approaches' under 'The Lighting Design Process')and probably revised it and cleaned it up, unifying some elements, adding others, following talks with the director and designer and further thought.

- Drawing the Basic Setup

You need to align the set and theater plan with the ceiling. You won't need all the details that appear on these plans; for instance you will only need those parts of the set that are relevant for lighting (walls, doors) . You don't need to draw all the lighting pipes, you'll only be drawing the ones that you need. (Jeff says: I find it helpful to draw even the unused pipes so as to provide greater clarity to the electricians.) Section III describes how to decide on those. Some theater plans include all the lighting pipes marked out at the side of the plan, and you can then extend only those you need to the entire width of the plan.

You don't want to draw irrelevant information because eventually the plan will be crowded enough with necessary information.. If set and ceiling plans are not to the same scale, decide on the scale with which you want to work. In Europe customary scales are 1:24 cm (1 centimeter represents 24 cm) or 1:50 for larger stages. In the US a customary scale is ½':1' (half inch represents a foot) or ¼':1'. (See 'Graphics')

Start out by drawing the set line (curtain line) and center line. If either of your plans doesn't have a set line, you might draw the rear wall. The point is to make sure that the set and ceiling plans coincide, by aligning features that appear in both.

You do not need to draw all the details that appear in the set plan, but only those that will affect the way the lighting is hung. Your lighting plan is a guide for the electricians who hang the lights and should only include relevant information. This means that you'll probably need to draw any walls that appear in the set. However you won't need to draw all the furniture, for example, but only things that are directly relevant to positioning of light. For instance you might need a fixture to be hung exactly over the center of a table.

- Turning Lighting Elements into Fixtures on a Plan

This is the hard part, though some CAD programs can make it easier. Your lighting element might be one special spotlighting an actor, or a large block of lights. For instance you might have a lighting element called “warm backlight: sun through window and spreading through the room.” You've decided you want this to be made up of two different subelements: the lights indicating the actual sun from outside, and another element inside the room giving the feeling that it's sunlight from outside. Now you have a few decisions to make (some of these you've probably made already):

- What kind of lamp? You decide what kind of instrument you want for each of these. You might decide, for instance, that the sunlight from outside needs to be PAR Medium Floods (CP62) because you want a sharply directional yet diffused feeling. The light inside might be 2 KW Fresnels, to give a more uniform and diffuse effect.

- Color? All the sunlight fixtures don't necessarily have to have the same color; you might want those closer to the window to be yellower, for instance.

- Channel assignment. (In some cases, it might be better to save this till after doing section IV, placing the lamps on the plan.) Do you want all the lamps of this element to work together? This is generally a bad idea unless you have a limited amount of dimmers. (Jeff notes: In this case, it's still a bad idea, but unavoidable.) It's best to have as individual control as possible, on the other hand grouping things together can make it easier to design the lights. When doing the lighting cues, you will use the elements of light as your palette. That is, you will generally bring up elements or blocks of light rather than individual lighting units. In this example of sunlight, you would certainly want the light outside the window to be on a separate channel than the lights inside, because it has a different job, and also because it's a different kind of fixture. Then you might want the units close to the window to be on a different channel than those further away. You might want a separate channel for the downstage units, or for those which hit the scenery.

- Where to put them? This will be much easier to understand if someone can demonstrate it to you, the guide below is intended just to give you the idea in principle. Here are three examples:

- Easiest example: an actor is standing center stage and you want to light them from the front.

You are working in two dimensions: from above as a bird's eye view, which we will call the horizontal dimension, and from the side, which we call the vertical. Start by choosing a horizontal angle. In this case you have decided the actor should be lit directly from the front. On your ground plan mark a little X where the actor stands, and draw a line along your horizontal angle. In this example, your line will coincide with the center line: it will run from downstage, through the X and back upstage. On this line mark everything that it touches: front of stage, rear wall of set, etc.

Now draw a section. This is a vertical side view, where the floor of the stage will be along the line you have drawn on your ground plan. Obviously it should be to the same scale. Here you reproduce everything that intersects the line on your ground plan: the set with the window in it, the edge of the stage, furniture. This should also have a line at head height, and I generally add some stick figures with heads to represent people.

If your grid is at a fixed height, you put the grid in on top. Otherwise there will generally be a height at which you've decided to put your lighting pipes, due to considerations of scenery and masking, and you should lightly draw a line parallel to the floor at that height.

Now draw a line from the actor's head up towards the lighting grid or pipes, at the angle which you want to light. Supposing you are trying for a dramatic effect, and you know you want an angle slightly steeper than natural, say 60 degrees. This means there is a 60 degree angle between the line you are now drawing, and a line parallel to the floor but at the actor's head height. Your fixture will be along that line at grid height. Drop a perpendicular from your fixture to the floor. Now you know exactly at what distance from the actor, along your floor line, you will place the fixture.

You will have details for your fixture such as its beam angle, and you can actually draw the light emerging from the fixture. You will see from the drawing just how wide an area the light will hit. You will see how far it lights the floor behind the actor, etc. Based on this you might want to change your choice of fixture, or lighting angle, or decide you want barn doors, and so on.

Go back to your ground plan, measure that distance along the line you drew for your horizontal angle, and draw in the fixture. That is where it will be hung.

- General front wash of the entire stage. First repeat the process of example (a) to find out how large an area your choice of fixture will give you. You can add fixtures to your section from example (a) until you have a side view of the entire acting area along the center line, and you can check the overlap between areas. Then mark out circles of this size on the ground plan, until the entire acting area (not just the center) is covered. Your section will give you the distance from fixture to area along the center, and you can just copy the same distances for all your areas. You might want to draw a special section for problematic areas, at the edge of the stage, or along pieces of scenery.

- Sunlight. Suppose you want your sunlight to come along a diagonal from a window upstage right. Draw a line on your ground plan along this diagonal.

Now draw a section. As before, the floor of the section will be the line you have drawn along the diagonal on the ground plan, and you will include a side view, to scale, of everything which intersects this line.

Now it is time to decide on a vertical angle for your sunlight. You can sketch at first, trying to decide what angle you want the light to come from. Let's start with the light from outside. You can draw the light coming in through the window, and you will be able to see what distance and height the fixture will have to be hung in order for the light to reach in past the window. Since the drawing is to scale, you'll also see how far the light will reach on the floor, and whether it will be able to light people standing at the window. You will have the details of the fixture you've decided to use: you will know, for instance, the beam width of your PAR MFL, and you can actually draw the beam.

You'll want your next fixture to light someone further inside the room. This will have to be hung onstage of the set wall, and you can decide how steep you want the vertical angle to be. Since you know the beam width of this fixture too, the drawing will tell you how large an area this fixture will be able to light.

You can then reproduce this area along the entire line in your section. Say the onstage fixture lights an area around five feet in diameter. Draw another area further along the line, and place another fixture at the identical distance from the second area as your previous one has been from the first area. Repeat the procedure for the entire section.

Then you can go back to the ground plan, place the fixtures at the distances you have found on your section, and add more areas till you have covered the entire acting area.

It is important to stress that we light actors' faces, not the floor! That is, the area size is taken as the area where the light hits the actors at head height!

For all elements, you follow the same principle: decide on the horizontal angle from which you want to light the target, then decide on the vertical angle in a section. The section will give you information on the path of your lighting beam, and the distance and height at which it should be placed. Then return to the ground plan and draw the fixtures.

- Easiest example: an actor is standing center stage and you want to light them from the front.

- Drawing the fixtures. Till now, you may have sketched your fixtures lightly on the plan. At this point you need to locate them precisely, and add details on channels, color etc. You also need to erase all the circles and lines you've used as temporary aids.

Your sketch from the previous step will probably not have all the fixtures along the same lines. You will need some compromise: if you have a grid, the lights will have to be moved to the grid. If you are using lighting pipes, you will can move the positions of your fixtures – some a little forward, some a little back perhaps, so that they are on a reasonable amount of lighting pipes. Usually variation of about a foot does not make much difference.

In a theater with fixed front of house bridges, you don't need to draw the FOH positions to scale because there is no chance for misunderstanding, and no possibility to rig the front of house fixtures elsewhere.

Important: IF a particular position is really important, you can generally find a way to put a light there! If your section convinces you that you absolutely must have a fixture just between two grid points, you might be able to rig a short pipe on the grid so the fixture can be just at that point. It is rare that a fixture must absolutely be at a certain position, but not impossible. Constraints of scenery could lead to this, for instance.

Fixtures should be drawn to scale. Templates are available for most CAD programs (and Jeff has, on his website, a set of symbols which will work in most CAD packages), and when drawing by hand you can either get hold of a template or make your own. Drawing the fixture to scale protects you from hanging too many lamps on a pipe where it won't be physically possible to put them.

Fixtures should be drawn pointing in the general direction they are to light. Again, this will ensure that there is enough room to hang them properly, and hopefully they will indeed be rigged in that direction as they're drawn, which will save time when focusing. There are few things more annoying than beginning to focus and finding you have to turn the fixture around, or that there is not enough room to point it where you want it to go, because a neighboring fixture is in the way.

Every fixture has additional information: its channel number and its gel (color filter), and — depending on the theater — its dimmer number and perhaps a socket or circuit number as well. In some situations the chief electrician will add this information as the lamps are rigged. The designer must indicate channel number and color. These should be marked in a consistent position. For instance channel number could be within the drawing of the fixture, and color filter number could be next to the lens.

- Legend:Your plan must have a legend, labeling the fixtures you have used, so that it will be clear that the drawing with the jagged edge is a 1 KW Fresnel, the drawing with jagged edge and two lines at the bottom is a 2KW Fresnel, and so on. Your legend should include a fixture with a channel number and color filter number drawn (and dimmer number if that appears too), so that it will be clear what these represent on the plan.

- Label: Labels vary, but your plan must be labeled with the name of the play and theater, with your own name, with the date, and with the scale used. It is customary to add the director's name as well. I also add my phone number, in case I'm not present when the lighting is being rigged and it's necessary to get in touch with me.

Create the Perfect Stage Plot and Input List

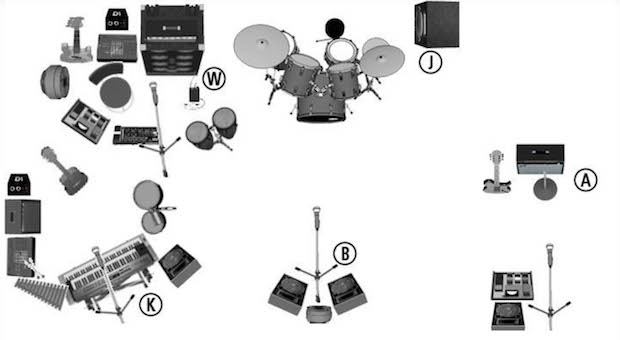

We created a stage plot designer that makes it quick and easy to put together the perfect stage plot and input list for your band or music group.

Any performing musician need to be equipped with an accurate stage plot to provide to venues. Make life easy for venue staff and sound techs by creating a professional looking stage plot and input list with this simple, customizable template!

Stage Plot Maker

Features:

Band Stage Plot Maker

- Easy to use Microsoft Excel template

- 31 unique instrument and equipment icons

- Input list for up to 24 inputs

- Space to include additional notes and information

Boss Stage Plot Maker

Download the Stage Plot Designer for free!